September 6, 2014

Day 11: Deschutes National Forest to Fremont National Forest

It's 30 degrees again when we wake up, but on this morning we force ourselves up and out of the sleeping bag just as the sun starts to hit the rain fly. We continue south layered in jackets and pants and gloves, but still with frozen fingers and toes, surrounded by a landscape that's very different from anything we've seen so far.

Gone is the tunnel of pine trees. In its place we see rocky outcroppings and the valley floor covered in the yellow and pale blue-green of sagebrush and bitterbrush. At the road's edge, the combined outline of us and our bicycles appears in a long shadow as the sun creeps up over the horizon, and vultures sit in groups of four and five on the fence posts. It all reminds me of the high desert regions of New Mexico, with the yellows of the valley blending up into mountains turned dark green from all of the pine trees.

| Heart | 0 | Comment | 0 | Link |

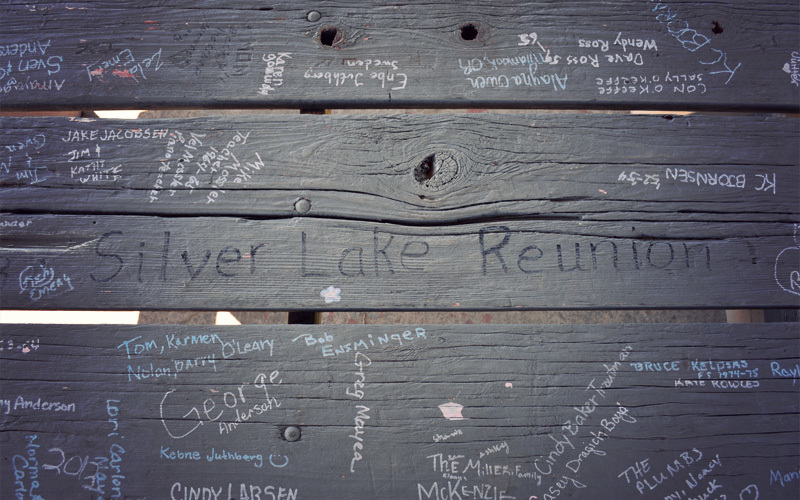

We bang over narrow frost heaves but move with a good pace along the gentle climbs and descents of Highway 31. It brings us to Silver Lake, population 149, in the middle of the morning. There's exactly one open business: the small grocery store. But it's well stocked with food both healthy and not, and that's what we came to find. And the tiny town park turns out to be great, giving us green grass and shade in which to rest, and both water and electricity to fill our reserves for the days ahead. Around us are the sounds of life in rural Oregon: sprinklers chattering, goats bleating, and the fart-like puttering of a riding lawn mower traveling back and forth on a patch of grass that needs nothing more than a modest push-mower.

From Silver Lake we head south on paved Forest Service roads across massive sweeps of dry, dusty, wide-open land that used to sit under water as part of the northern reaches of the Great Basin. Jackrabbits shoot off into the brush as we pass, dragonflies bounce off our shoulders, and click beetles stutter and dart with what seems like no direction in mind under the bright midday sun.

For about five miles we ride like the click beetles, angling left and right, all over the road, with no obvious pattern. It's not that we're drunk, it's that every 50 feet the road splits in front of us with frost heaves almost a foot wide. They extend the entire width of the road, and although they've been patched in the past, the job was done so long ago that the heaves have expanded and it's like the patches don't exist. That means a jarring whump-whump every ten seconds going up the hills and every two seconds going down. They rattle every cable, bolt, and pannier on our bikes and leave our arms, wrists, and shoulders sore from the constant impacts.

But then, seemingly at random, the surface changes a bit and the road becomes smooth, unbroken, unlined blacktop. Bitterbrush grows thick and in deep yellow tones at its edge, where the plants thrive on the rain water that flows down off the pavement and settles in the dirt beyond. We see more tiny chipmunks, but out here they don't charge off into the bushes right away, because so few cars come this way that they aren't a constant threat. Today, even though it's a beautiful Saturday, vehicles pass us no more than once every half hour — and all of them are American-made extra-cab trucks with layers of dirt and dust all over.

As we continue on all alone, I think about the guy in Bend, who said something to Kristen about living the dream as she rode past. And here's the thing: he's right. If I inherited five million dollars today, I'd still be out here tomorrow, with Kristen, doing precisely what we're doing right now.

The road rises and falls like waves, but always trends more up than down. We crank and crank and crank for hours, with good strength at first, but then flagging as we close in on the top. When we get there we don't find a sign or a marker or anything that tells us we've climbed to 6,200 feet — almost a thousand feet higher than McKenzie Pass — just the road turning a little to the left and picking up a slight downward lean. There we stop to eat a small dinner, and that's when it hits us how wasted we are. Our legs feel weak, our mouths are dry, and all we want to do is fall asleep. It turns out that working so hard, for so long, at such a high elevation comes with a big cost. At least we know that it's all downhill for the rest of the evening.

Except I read the elevation profile the wrong way.

In fact, we aren't at the top. We coast down a short drop after we finish eating, but then we start going up again.

It goes on like this for four more miles. Somehow we find reserves of energy that power us on to a Y in the road, where we head right and at last start down for real, with the light almost gone from the sky. Of course our reward isn't smooth coasting down the mountainside, but a gravel road. The surface is kind of packed, but not so well that we're able go above about twelve miles per hour without a wipeout becoming a serious concern.

After two miles of this we're done, done, and done. We head a hundred feet off the road into the woods and set up among a bunch of dry old pine trees as owl hoots echo down the mountain and a few free range bulls moo every couple of minutes in the distance. Because we're still more than a mile above sea level we know it's going to be a cold night, but we hardly even think about what the morning might bring. We just throw on a few extra layers and fall dead asleep in moments.

Today's ride: 61 miles (98 km)

Total: 460 miles (740 km)

| Rate this entry's writing | Heart | 2 |

| Comment on this entry | Comment | 0 |