February 18, 2008

Give this man a stiff drink and a talking-to

SAN DIEGO DE LOS BANOS - I think Pilo could see by the look of me that I wasn't likely to go any further next morning. And that I could do with a drink. "I'll call round and see you in the afternoon," he told Steph, recognising that communication with me was pointless. "If you're still here, fine. If you're not, well I'll have had a good ride, won't I?"

And so Pilo rode up to our room in a three-bedroom tourist area and propped up the bright blue and white mountain bike that it had taken him 10 years to save for. When he had the money, he found a tourist who didn't want to pay excess baggage on taking his bike back out of the country and he bought it from him. It is just about the smartest bike in Cuba and there's no disguising Pilo's pride in it.

"It's a British bike, you see?" he said. "A Raleigh."

| Heart | 0 | Comment | 0 | Link |

Pilo teaches English in the village school. He rides six kilometres from a neighbouring town, does his teaching and then rides home again. Sometimes he teaches at the regional university, too, which means a ride in another direction.

"I could get a ride in a passing lorry," he said, taking pride in using the British rather than the American word for a truck. In Cuba, the shortage of transport and fuel means drivers of all sorts but especially of lorries pick up passengers beside the road. It's a legal requirement, in fact, but it's clear that it's done willingly and in a spirit of co-operation and perhaps in a thumbing of the nose at giant neighbours who, as Cubans see it, make such measures necessary.

"My wife hitches a ride to and from work every day," Pilo said, "but I don't like travelling like that. And in any case, I enjoy riding my bike and that keeps me fit and healthy."

Pilo is a man who smiles a lot, who speaks totally fluent English, who knows more of British history than I ever learned when I lived in Britain, but who has never left Cuba. With him he brought a small handful of tourist postcards of London. He handed them to me with pride, let me look at them and then, with still more pride, named the streets and buildings. Only once was he unsure of himself.

"I think that's Westminster cathedral, isn't it?" he asked. And of course he was right.

I offered him a drink and we agreed to go to the town's larger hotel, the other being shut for restoration.

"To be truthful, you were wise to stay here and not there," he said. "It is a lot more expensive there and the quality really isn't good."

We got up and started walking up the slope to the main road through the village. After a minute, he took us into a courtyard, opened a faded wooden door of the sort you'd have on a shed, wheeled his bike inside and gestured us to follow.

We walked not into a shed but what I think was a room at the back of a building. It was small, unlit and slightly musty. It was also full of books.

"It's my school library," Pilo said. "The books are all rather old now, I'm afraid, and we have a lot of bookworms."

| Heart | 1 | Comment | 0 | Link |

I looked around. Most of the books were paperbacks, or at any rate not hard-covered. I recognised some names but many meant nothing to me, especially those of some sort of eastern European origin.

"Most of them came from the Russians," Pilo explained. That was in the era between the start of the American embargo and the arrival of Mikhail Gorbachev and the change of heart in Russian foreign policy. After that, when Russian support vanished in an instant, Cuba went into a crisis now called euphemistically "the Special Period" in which the return of starvation looked possible.

"You can see that some of the books are now so old and worn that we can't use them any more."

I spotted a Spanish edition of The Sea Wolf, by Jack London.

"He lived in Alaska," Pilo told me instantly. "That's where he drew all his material. Education is our great pride in Cuba. That and the free health care for everyone. I am very proud of our schools. I teach English as much as I can through history. History makes interesting stories and that makes learning a language interesting."

We returned to the warmth of the afternoon, leaving Pilo's bike locked in with the books. On the way out of the courtyard, I pointed at what I had noticed on the way in: a small, fenced enclosure of fine, grey gravel on which sticks and branches had been built into knee-high structures that I remembered from my youth.

"It's the scouts," Pilo said. "It's all the different ways to make a fire and cook on it when you're camping."

And sure enough, it was, straight out of Scouting for Boys. All it lacked was Baden-Powell's advice to suck a stone to hold off sensations of thirst and his stern but unexplained warnings against "beastliness".

"Is that the scout hut, then?" I asked.

Pilo smiled. "No, it's the back of the police station!"

There are policemen everywhere in Cuba but nobody seems in the least bothered about them. We did see two policemen searching a teenager one night in Havana but apart from that the role of the police seems to be driving around or just standing about smiling and waving at anyone who smiles and waves at them. The only times, apart from the teenager, we have seen them doing anything were on the larger roads, where every so often there'd be a gantry across the highway and a couple of offices on each side of it. Drivers slowed down, were generally waved on, now and then stopped. We never did find out what the checks were for. I can't imagine that brakes and general roadworthiness or emission standards figured all that prominently because they'd be asking a bit much of the majority of Cuban vehicles, many of which look as though their internal structure could depend heavily on string.

It's against the law for a Cuban driver without a permit to transport a foreigner, although I can't tell you why, but surely it would be beyond a poor country's will to install expensive checkpoints across the country just to catch the occasional driver giving a lift to a Canadian (Canadians are the most numerous of foreign visitors to Cuba) or a lost German.

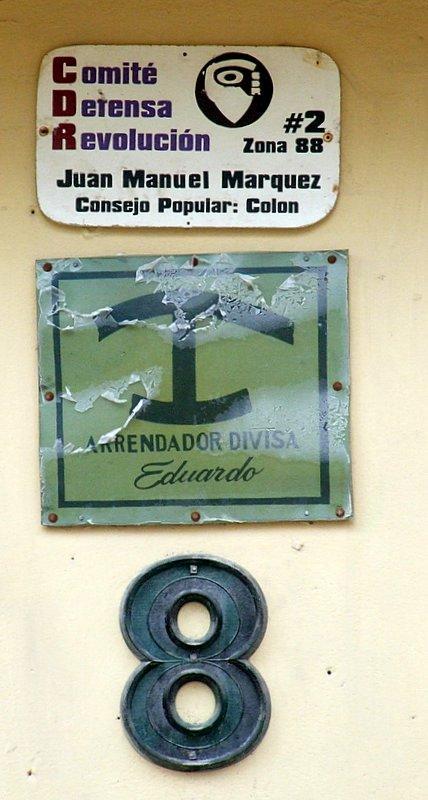

A more curious feature of the Cuban landscape is the omnipresent office of the Committee for the Defence of the Revolution. Every block has one, just another small building and a single doorway like all the others, and you'd think they were oppressive until you spot that now and again they also have the little emblem to show they're licensed to take in foreign visitors.

| Heart | 0 | Comment | 0 | Link |

I never did quite understand Pilo's explanation. At one end of the interpretation, they are Stasi-like controls and snoops on the communist qualities of the population. And for all I know, perhaps there is indeed someone inside with a notebook and Fidel Castro's phone number. On the other hand, you can't become a communist just like that in Cuba.

"You have to be invited to join," Pilo said. "You can't just sign up."

"Do you have to be a member of the party to get a good job?"

"No, it makes no difference."

On the other hand, of course, you can't stand for election unless you're a member of the party because it's the party that selects all the candidates. And I get the impression that potential members are noted even in their school years, just like gymnasts used to be in East Germany and Romania.

The Committee for the Defence of the Revolution, I never did understand. One for each block, each set of apartments, would seem excessive in even East Germany. And you'd think they'd do better for themselves than the shabby places they work from. And they can't spend all their time just snooping and making notes and denouncing people because, first, there's not enough room for all the people it would take, second because you'd think it contradictory to pry on Cubans yet offer foreigners a bed for the night, and third because the CDR office is where you go if you want a flu jab or some other treatment.

| Heart | 0 | Comment | 0 | Link |

I thought a couple of rums would clarify the situation but it never did and I was pleased to have the interruption of a bunch of sweating Czechs on mountain bikes, enjoying themselves on a cycling Prague Spring. They'd been booked into the hotel, which I hope they were happy with after what Pilo had explained about it, and they'd been followed everywhere they went by a blue and white bus. Not my idea of cycle-touring but then I don't suppose they got themselves into the state that I got myself into yesterday either.

| Rate this entry's writing | Heart | 0 |

| Comment on this entry | Comment | 0 |