June 24, 2011

Day 73: Montrose, MO to near Walnut, KS

On the outskirts of town I ride past a field full of at least two dozen cows—some black, most brown, a few white. A couple of them let out concerned moos and most watch me with suspicion, but they manage to stay mostly calm until one starts to run away, and then all of the rest follow right along. The early morning sky glows equal parts pink, purple, and orange, and off to the east I see the hazy shadows of rain showers and the flashing of lightning. It's warm and windless at 5:30 a.m. I speed away from Montrose as quickly as I can.

| Heart | 4 | Comment | 0 | Link |

Just outside of Appleton City a late 1980s Ford truck with dark blue paint pulls up behind me. I assumed Ella would be passed out in her bedroom for the better part of the morning after destroying a rack of Busch Light last night, but she's crazy enough that it wouldn't surprise me if she took to the highway to track me down and tell me one more thing about her incredible grandson.

"Good lord, no!" I say to myself as the truck hangs about a hundred feet behind me.

As soon as the oncoming car passes, the Ford pulls alongside—and then speeds by, the driver probably on his way to work.

I breathe a huge sigh of relief.

On one ten-mile stretch not a single car drives past. There's no wind noise and no airplanes fly overhead; all I hear are the different kinds of birds talking at once. A few bands of showers pop up along the way, but they're so small that I can pedal through them in just a minute or two. By the time I reach the town of Rich Hill at 8:00 I've done 32 miles of riding and averaged 14 miles per hour, both of which have to be some kind of personal record. Normally I ride slowly, take my time, and try to get lost in the details of the world around me. But today's not most days. Not only are the roads flat, but it's cool and overcast and windless. There might only be two or three days like this throughout the entire summer. I know I need to make the most of this amazing gift. It's time to mash.

A few miles up the road I pass an Amish family headed the opposite direction in a horse-drawn carriage. From the looks on their faces I can tell that we both think the others' chosen mode of transportation is ridiculously strange and slow. Not much farther on the wind finally kicks in—but it's from the east! I laugh out loud and nod my head in approval as the flat miles fly by and the breeze helps push me toward Kansas. Hawks scream and circle above me, a family of white-tailed deer dash into the woods in the distance, and fields of corn stretch in tightly spaced rows of dark green for hundreds of acres on all sides.

The town of Hume is a completely depressing place five miles from the state line. It's not quite dead, but it's on life support and its loved ones are about to pull the plug. The small park that sits at its center is clean and attractive, but it's surrounded on all sides by old brick buildings, most of which have boarded up windows and doors or interiors filled with the dust-covered reminders of businesses that once were. After a grand entry into Missouri, riding over the Mississippi River and looking out on the Gateway Arch and downtown St. Louis, it says goodbye with a feeble wave.

Every state I've traveled through has left a distinct, well defined impression in my mind. But as I pedal west and think back on my time in Missouri, the picture is mostly vague and fuzzy. My experience in St. Louis with Tery and Danny still resonates strongly, but the biking bubble of the Katy Trail and the wind-blown country towns of the western half of the state hardly left a mark. I feel like I mostly passed through them in an invisible shell, as an observer and not a participant. Riding through Missouri was often more of a trip through my own mind, where I spent hour after hour lost in thought and occupied with the people I love, my work, what I want from my future, guilt, heartache, singing and talking to myself, and doing my best to battle boredom.

I cross the state line and cruise exactly to the west. I sing "Carry on My Wayward Son" because it's by the band Kansas. I spend an hour trying to come up with some other Kansas-themed music but draw a blank, so it's "Carry on My Wayward Son" over and over and over again. The scenery around me all looks much the same, too. It's as if my life has turned into a four-minute movie that runs in a never-ending loop.

I make the plumbing cry uncle at a beautiful, century-old library in the tiny town of Presoctt before loading back up on honey buns and gas station pizza. Their appeal is wearing off after ten weeks on the road, but none of the dying towns I pass through have grocery stores or restaurants, so my options are limited. The energy powers me south on Old Highway 69, a road now used so little that there's no center stripe. The countryside around me seems very un-Kansas, with rolling hills, plenty of trees, and far more green than yellow. The hills turn out to be steeper and more frequent than in the part of Missouri I just left, and I wish for the flat Kansas of stereotypes.

"I Heard it Through the Grapevine" blasts from the speakers at the diner in Fort Scott. Over grilled cheese sandwiches covered with mashed potatoes and gravy I tap my right foot and hatch a plan to take advantage of the last tailwind I might see for a week. I decide to make a huge push to the southwest and join back up with the TransAm in the city of Chanute. It's a ridiculous idea. Not only is the town 50 miles away, but I'm running on four hours of sleep and have already bagged 70 miles. That's what the wide open, windy plains of Kansas and the promise of easy riding do to normally reasonable bike riders.

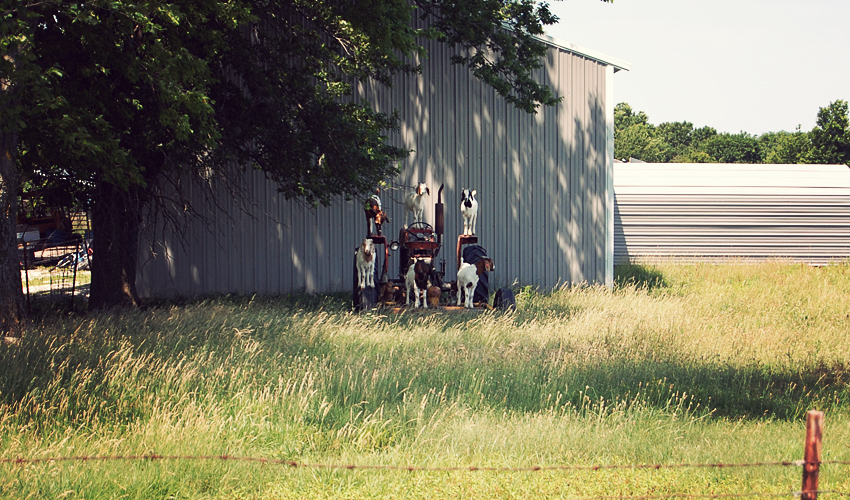

Unfortunately the state continues to forget that it's supposed to be flat and feeds me a steady diet of hills that turn me into a sweaty, surly, swearing mess. All around me on a quiet country road I see fenced-in fields of uncut grass and ugly-looking shrubs, where low mounds gently rise and fall and old grain silos made of brick stand empty and forgotten. Eventually the pavement gives way to well-groomed gravel, which takes me past herds of cattle that have never before seen a bicycle rider. It must be terrifying, because it leads to the splashing of water, the crunching of low-hanging tree branches, and the thundering of hooves as thousands of pounds of frightened beef haul ass in the opposite direction.

The tailwind falters at first and soon dies completely. The dream of reaching Chanute goes along with it. As the heat goes up, fatigue and mild dehydration set in. The landscape turns flatter and more wide open, but I'm so worn down I hardly notice. I'm jealous of the cows that stand knee-deep in a dirty and disgusting pond. I ride slowly. My mind turns hazy.

The odometer rolls over to 99 as I pass through the dying town of Hepler. I want so badly for a cold bottle of water, but the only open business is a bank branch, the smallest I've ever seen. I'm about to yell out something terrible in frustration, and then I see it: a soda machine, shining like a blue and red beacon of hope, just to the left of the garage door of the volunteer fire station. When I find out that it is at the same time plugged in, not sold out, and only wants 50 cents for a can, I make some weird, embarrassing noise of excitement. A Pepsi and two Mountain Dews go down the hatch like it's nothing. It's not ideal hydration, but if anyone was around to give me crap about it I'd tell them to shut their filthy mouth. In that moment it's perfection.

A couple of middle-aged guys walk from the bank to their truck. One of them asks me if I want a beer and I can't say yes fast enough. The guy to my left wears a mesh ballcap and sips his Busch from an old blue drink cozy, while the other stands in dark blue overalls and a gray t-shirt with the tattooed name "Karla" peeking out from the bicep under the left sleeve. I ask if Hepler has any other stores and they say no. Then I tell them that it looks like something used to be here, where all of the boarded-up buildings now sit.

"Yeah, there used to be," the second guy says, "But then we lost our school. And then the railroads consolidated. We used to have three restaurants, two gas stations, and even a motel if you can believe it."

I almost can't. The place is as barren as any town I've seen, and I've seen loads of them on this trip.

"Now we're down to about 150, if you count the stray dogs and cats. But we have good people. It's a good community. It's a sleeping town—everyone works somewhere else—but it's a good town."

Good, but nothing like what it once was. I wonder if that matters to the few dozen families who stuck around.

I meet up with the TransAm and backtrack a mile and a half east to the Immanuel Lutheran Church, a beautiful, bright white place set among fields of corn that's been hosting touring bikers for years. Two women working outside greet me and tell me to make myself at home. Inside I check my phone and find that I have a new voice mail message. Instantly I recognize that the phone number belongs to the client I met with back in Seattle. My anxiety builds to a borderline unsafe level over the next 45 minutes as the weak cell phone signal drops the connection over and over again, teasing me with the first 20 seconds of the message before falling dead every single time.

Maybe the wind finally blows the right way, or maybe all of the horrible things I yell at my phone finally make a difference. Whatever the reason, at last I get through.

The contract is mine.

I throw my head back, close my eyes, pump my fists a few times, and let out a deep sign of equal parts satisfaction, relief, and exhaustion.

I celebrate with cheap French vanilla ice cream from the freezer in the kitchen and one of the cans of beer the guys back in Hepler gave me. I clean up and relax in the gathering hall, a giant space with high ceilings and sparkling linoleum floors. Folding metal chairs surround six large tables, on top of which sit a pair of salt and pepper shakers and a bottle of hand sanitizer. A few prints of religious scenes hang on the walls and an old piano sits in the far corner. The room can hold almost a hundred people, but tonight there's only one.

It's completely different from last night. I feel welcomed and trusted, taken in by a community that's opened one of their most sacred places to me, even though they don't know me and I'll probably never be here again. Unlike the school principal in Montrose, they choose to see the good, to believe that great things will happen instead of the bad, and to lend a hand to travelers trying to achieve a difficult goal. The generosity sends me to sleep smiling, my heart filled with joy.

Today's ride: 105 miles (169 km)

Total: 3,554 miles (5,720 km)

| Rate this entry's writing | Heart | 4 |

| Comment on this entry | Comment | 0 |