July 28, 2011

Day 107: Dupuyer, MT to East Glacier Park, MT

I'm on the road by 6:15 and find that this part of the country is so much more beautiful when the wind isn't howling. Out to the west I see snow on top of the Rockies, which keep getting larger. To the north and east, textured hills rise and fall and cast deep shadows in the first light of the morning. Few cars pass by and Montana is quiet except for the hawk that screeches at me from on top of a telephone pole.

But within an hour the winds return. I knew they'd be back eventually, but figured they'd ramp up little by little and give me a few more hours of decent riding.

I was wrong.

In an instant I pick up a sidewind that comes at me with almost as much strength as the biggest breeze from yesterday. The joy of the morning ride blows away with it and the grind is on. Five minutes later I curve left so that the wind blasts me in the face, and then almost immediately start to climb a long and steep hill. It's about this time that I lose my mind. Awful words tumble out of my mouth in an avalanche. I growl in anger. I yell at the hill, at the wind, at the entire state. When I try to catch myself and power through it like a responsible bike tourist I only buy 30 seconds of calm. Then it's back to the swearing, spitting, sweating disaster that pushes west at five miles per hour. If someone else was with me, or if there were more cars and trucks passing by, I'd find a way to keep it in check. But on my own, out in the vast emptiness of the Blackfeet Reservation on an open rural highway, the froth and fury pour out unchecked, with a passion I never knew I had. It's a bad, bad scene.

Farther on a semi truck almost takes me out—as in tires on the edge of the white line, within five feet of the bags, enough to startle me and send the bike into the gravel, and cause me to consider death as a possibility out here. Up the very next hill I'm chased by dogs for the first time since somewhere in Illinois. All the while, the wind continues to get stronger and makes every hill a few percentage points steeper. The morning becomes less about enjoying the ride and more about answering the question, "How many more miles until Browning?"

| Heart | 2 | Comment | 0 | Link |

I'm crawling slowly up the 18th hill of the day when out of the corner of my eye I spot a dog following me in the shoulder off to the right. Back in Kentucky I learned that it isn't the barking and howling dogs that I have to worry about, but rather the ones that run up from behind quietly, in stealth, looking to launch a surprise attack. For a split second I'm ready to crap myself, but soon I notice that he's not out for blood. He's just a tag-along, jogging beside me at the same pace with his tongue hanging out of the left side of his mouth and his tail wagging. Then I realize that he isn't alone. His brother, another brownish-black dog that's part German Shepherd and part four other breeds, trots along ten yards behind. It's unusual but not surprising, because in the hour since I entered reservation land I've seen dogs, cows, and horses all wandering on the highway side of the fence line.

I figure they'll turn back and head home after a minute or two, because most dogs do. But these are not most dogs. For more than a mile they keep up with me—sometimes ahead, sometimes behind, sometimes dead even. It works out ok until I stop, which causes them to lose their focus and start moving in different directions. It sets up a dangerous scene with dogs drifting across the highway, cars and trucks slamming on brakes and blasting horns, and me in the middle of it all hoping I don't get run over in the chaos.

As far as the dogs are concerned this is the greatest thing to happen in a month and they're going to follow me all the way to Washington. I can't do anything to shake them. The hills force me to ride slow, and the wind slower still, which means that all the dogs have to do is jog. Four times I crest a hill, praying for a downhill that will let me fly ahead and ditch the stragglers, and four times I'm met with more up. All the while they run into the road, pick at roadkill, and crawl below the fences on either side of the road and chase after the cows. It's ridiculous, but because I know that it'll only turn worse if I stop, I keep riding—mile after mile, up and up, straight into the wind. The dogs are dumb and sweet and I would love to take them home with me if I could, but in the moment all I can do is say awful things about them and about their mothers. It's the cherry on top, the icing on the cake, of the worst morning on this trip.

After almost ten miles the curtain comes down on the rolling circus. I come to the top of a rise, spot Browning in the distance, and see a long downhill in between. I mash the pedals like I'm being chased by the devil, shout out "See ya, suckers!" and fly north with the two brown blurs in the mirror gradually becoming smaller and smaller until they disappear completely.

I pedal past modest one- and two-story homes and into Browning, which is the only major town on a Blackfeet reservation that covers more ground than the state of Delaware. Half of the businesses are open and half are closed for good. I see a lot of people walking the streets, many less than sober. All of the schools and community centers and college buildings are modern and pristine, but most everything else looks somewhere between tired and completely worn out.

For a few minutes I stand over the bike in a parking lot away from the main road through town and take some notes. In that time I'm hit up for money, for the light of a cigarette, for anything at all, by several locals. It's just like I'm walking Third Avenue in downtown Seattle, except I'm biking through a small town in the middle of nothing in Montana, where things like that shouldn't happen. But they do—and with unemployment on the reservation near 70 percent, and 25 percent of the employed not earning enough to clear the poverty line, it's not something that's going to change. Ever. I feel worse for Browning than any place I've yet traveled.

The ride to the west becomes another slow crawl straight into the wind, but looking out at stunning mountains, colorful wildflowers, and wide open vistas dotted with grazing bison helps. Knowing I have just 13 miles to ride instead of 40 helps. No stragglers and no near-misses from huge trucks helps.

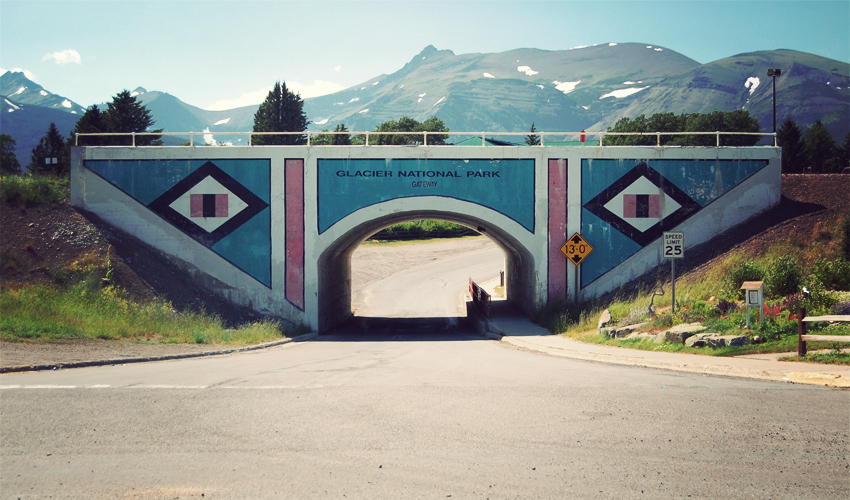

In the town of East Glacier Park I set up in the yard of the house owned by Sam, the first WarmShowers host I've stayed with since Missouri. He's a happy and welcoming guy who works as an EMS in the park during the summer and teaches technology courses at the community college in Browning in the off-season. He moved out to East Glacier 14 years ago from Indiana and tells me all about what it's like to live in one of the remote corners of America.

The town is full of people in the summer, but year-round it's home to less than 400, with only one grocery store, one gas station, and a couple of restaurants. And although the summers are beautiful, they're very short, and it's not unusual to see the occasional snow in July or August. The winters can be completely mental, with snow drifts that surround two sides of the entire bottom floor, 70 mile per hour winds, and temperatures that drop to 30 degrees below zero.

"Make sure to drink our bottled water," Sam tells me. "The town treats the creek water, but the system doesn't always work. Last year everyone in town got sick and no one could figure out why. We thought it might just be flu season, but no one in Kalispell or Browning was affected. It turns out a moose died in the creek upstream and the treatment system had failed and we were all drinking straight disease water."

Now that's rugged Western living.

East Glacier Park sits on the edge of the reservation, which brings in all kinds of complexity when it comes to land ownership, public utilities, and especially law enforcement.

"They say that if an Indian beats up an Indian, call the Tribal Police," Sam explains. "If it's a white guy and a white guy, call the County Sheriff. If it's an Indian and a white guy, the FBI might get involved, because it's all federal land."

Because Sam has spent so much time teaching in Browning, I pick his brain and try to learn more about the place. It turns out that although unemployment is ridiculously high, it's also very seasonal. The largest employer in the area is actually the government, but only in the summer, and only when they need help putting out forest fires. In an ironic twist on the native peoples' traditional way of life, it's actually a huge boost to the local economy when fires ravage the nearby land.

"They say that no fires in July means no presents under the Christmas tree in December," Sam tells me.

I ask him about the impact of the casino that I saw. Back in Washington State, casinos located around larger cities generate huge amounts of money for the tribes and provide a consistent source of income that a few decades ago didn't exist. That isn't the case here.

"They didn't have enough money to build it themselves," he tells me, "So they hired a developer to do it. That means they have to pay back the developer completely before they start getting a cut of the profit. But they don't make a profit. Some people stop in when they're traveling through, but not that many, because Browning's not that close to anything. In fact, most of the customers are people who live there, so not only are they not making any money, they're actually pulling money out of the community and making things worse."

I feel even more down on Browning. I didn't think that was possible.

We spend the evening watching a ridiculous Western TV show from the 1970s as the three cats—Boo Bear, Thomas, and Dust Bunny—turn the living floor into a jungle scene. I head out to the tent just before the sky turns completely dark. When I check the weather forecast and see huge winds for tomorrow I hang my head, say "Fuck it," and head to sleep trying to forget about it all.

Today's ride: 54 miles (87 km)

Total: 5,491 miles (8,837 km)

| Rate this entry's writing | Heart | 3 |

| Comment on this entry | Comment | 0 |